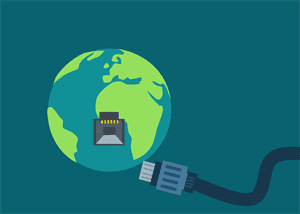

Aside from some limited satellite coverage, Tonga is reliant on one single submarine cable for all its communications with the rest of the world. It looks like Tonga may be cut off for some weeks while a repair ship races to the scene – and that that assumes of course that the repair can be made, and if the situation is still volatile it could mean further delays.

While nearly a million kilometres of submarine cabling has been laid around the world much of it connects northern hemisphere cities with each other. You could practically walk across the North Atlantic on all the fibre that connects the US eastern seaboard with the UK and Europe. Yet when it comes to those who would benefit most from connectivity – the truly remote parts of the world – the economics simply don’t stack up.

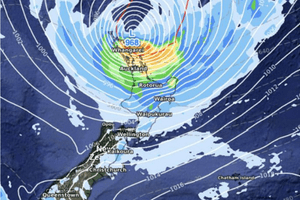

Until recently, New Zealand was in a very similar situation. We only had two cables (the two halves of the Southern Cross Cables network) landing 24km apart on the Auckland peninsula – literally on an active volcanic field. While we had enough capacity for New Zealand users to connect to the world, we lacked redundancy in terms of the number of cables and the diversity of routes by which the cables connect.

That was the case until the Tasman Global Access network connected Sydney with Hamilton and you may be alarmed to know that didn’t happen until November 2020. For the first time anything that took out the Auckland connection points wouldn’t mean New Zealand would be cut off from the world.

Since then the Southern Cross Cables and TGA networks have been joined by the Hawaiki Cable network and soon by Southern Cross NEXT, the replacement for the now aged Southern Cross Cables network, so New Zealand is now well served in both capacity and resilience.

/intl-cables-with-both-lines.png)

/intl-cables-with-both-lines.png)

It also means that New Zealand now has an excess of capacity and competition between providers, and we can start to use that to our advantage.

Companies like Google, Amazon and Microsoft are household names when it comes to software and online life, but they also host vast amounts of data for companies all around the world. These cloud companies store content in mega datacentres and in this part of the world those have largely been built in Australia. Now, we can start to entice them to New Zealand where they’ll find not only high quality capacity on our submarine networks but also relatively low land prices, green and cheap electricity, a relatively stable political environment and a skilled population. And on top of all that, we’re relatively cold and damp, which is a huge factor as air conditioning for the massive array of racks is a major cost for such things. Take that, Sydney.

Connectivity is now treated as an essential service both from a commercial point of view but also from one of resilience. As former Prime Minister Sir John Key pointed out in his recent opinion piece, we now have fibre to the home for nearly 87% of the population and our mobile coverage hovers around 98%.

These are astonishing figures when you compare New Zealand with other similar nations. The UK fibre rollout is stalled at around 25% of the population and Australia has only just passed 30% at a cost of a whopping $50 billion.

The next step for New Zealand is to ensure those in rural and remote parts of New Zealand aren’t left out. We have to consider how to reach those really difficult-to-connect customers and that’s going to mean a further public-private partnership.

I suspect we’ll see a combination of technology solutions, including the new satellite services that are coming onstream, as befits our long and wrinkly country, but we can’t not do it.

The UFB has been a dazzling success both in terms of what it’s achieved but also how it was delivered and we should be proud of what we’ve got. Now we need to look at the rest of the country and get them online as well.

By Paul Brislen, TCF CEO