The weekend before Cyclone Gabrielle arrived in New Zealand the Telecommunications Emergency Forum (TEF) was activated to coordinate the telco sector’s response. The TEF is a working party made up of the key network operators, retailers and other telco organisations that might be affected by any given emergency event. We feed information into the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) team who work out of ‘The Bunker’ – in the basement of the Beehive itself.

NEMA coordinates all information coming in from lifeline utilities (roading, water, electricity, telecommunications) and works with Fire and Emergency (FENZ), Police and Civil Defence among countless other agencies. Information flows to and from NEMA to better coordinate our responses and help each other increase efficiency.

In a business-as-usual environment, emergencies and outages are handled in-house by the affected provider. Anything from software issues to diggers pulling up fibre lines to cyber-attacks – telcos are quite good at handling such events because robust systems are in place to cope with crises. Telecommunications networks are complex beasts that need to be actively managed, which gives us lots of practice at speedy recoveries often without disruption to the public.

But where a problem is too big for one telco to handle, or where an issue affects multiple providers or takes place across multiple regions, we work together to ensure networks continue to run and customers are affected as little as possible. The COVID outbreak was a good example of this, with the sector working together to monitor activity levels and ensure customers would not be impacted with everyone staying home and using the internet.

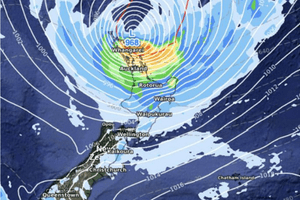

This cyclone came in hot on the heels of the worst flooding in Auckland’s history, so public focus was largely on Auckland as potential ground zero. But we knew from past experience that the Hawke’s Bay was likely to be in the firing line, so preparations began early.

Generator supplies were moved out across the regions and teams were placed on stand-by, but what happened next was one for the record books.

We were prepared for a regional response but the scale of the damage was bigger than any of us were prepared for. Never mind a regional state of emergency, a national state of emergency was ultimately declared as roads were destroyed, stop banks washed away, power lines brought down and a large part of the country knocked offline.

The Prime Minister called it “unprecedented” and you’d be hard pressed to disagree. Outages were reported from the Far North, Northland, Auckland, Coromandel, across the Waikato and Bay of Plenty regions and throughout the Hawke’s Bay and Gisborne where the electrical sub-stations were completely flooded, destroying the region’s electricity supply in a single night.

Telecommunications networks all need electricity to run. Whether mobile, fibre, copper or satellite, without electricity to power the network and equipment, calls and messages simply do not get through.

Some folk remember the “good old days” when copper lines were the only network operating and seem to recall the phone working even when the power was off at home.

That was true, however only if the power at the exchange is still working. In Gabrielle that wasn’t the case and once the batteries are exhausted (around four to eight hours) the lights went out across the country.

As mobile towers were were knocked offline in the 4 affected regions, actual damage to the cell sites was minimal. Generators were deployed to keep mobile towers powered which enabled vast tracts of the network to deliver some levels of communications to affected communities – in fact, 96 hours after we started our response work more than 90% of the towers were back online.

Copper lines don’t like getting wet and the electronics in the network were fried. Fibre lines continue to work under water so the impact was far less on the newer technology.

The other big problem was damage to the backhaul network – the major network connection between regions.

Fibre is very resilient, but when bridges collapse and the roads themselves slide off the hillside it doesn’t stand a chance. In this case all the major fibre connections in and out of the Hawke’s Bay and Gisborne regions were damaged or destroyed. In some cases gaps of up to 3km needed repair.

Fibre network operators have gone to huge lengths, in difficult conditions, to reconnect the backhaul network. Chorus had to fly a helicopter slowly along a ridgeline laying fibre out on top of the ground for engineering teams to splice in and patch the hole. It’s not pretty, but it meant we could reconnect the network and get the region back online as quickly as possible.

So where to from here? It’s important to review and identify any improvements to ensure we are even better prepared for the next emergency event. The scale of the destruction can be so much more than anticipated and I doubt we’ve seen the last of the big storms.

For now, I’d like to extend my thanks to the teams that worked round the clock to prepare for, and then respond to Cyclone Gabrielle. The TEF largely fills a coordinating role – the real work is done on the ground by the men and women of the engineering teams who pulled out all the stops to get sites back up and running. Technicians from one company would work on other network assets – fuel trucks would top up generators regardless of which cell tower they were powering, fibre technicians worked on broken fibre regardless of ownership.

There are always going to be emergencies to respond to and no two are alike, but we learn from each crisis and work to make the network better for next time. Because there is bound to be one sooner or later.