We live in the world’s second riskiest country for natural disasters. Between earthquakes, floods, tsunami, volcanos and of course extreme weather events, New Zealand is uniquely affected by Mother Nature, all of which makes providing networks in Aotearoa that much more challenging.

The annual National Lifeline Utilities conference, held in blustery Wellington this year, helps bring together a range of lifeline groups, critical infrastructure providers and others to consider how best we can all work to support each other. Emergency responders mingle with economists and policy makers. Telcos mix with roading and power providers. Volcanologists were in short supply this year, but the team from Toka Tū Ake EQC were there to remind us that we are still building homes and indeed whole communities in known areas of risk.

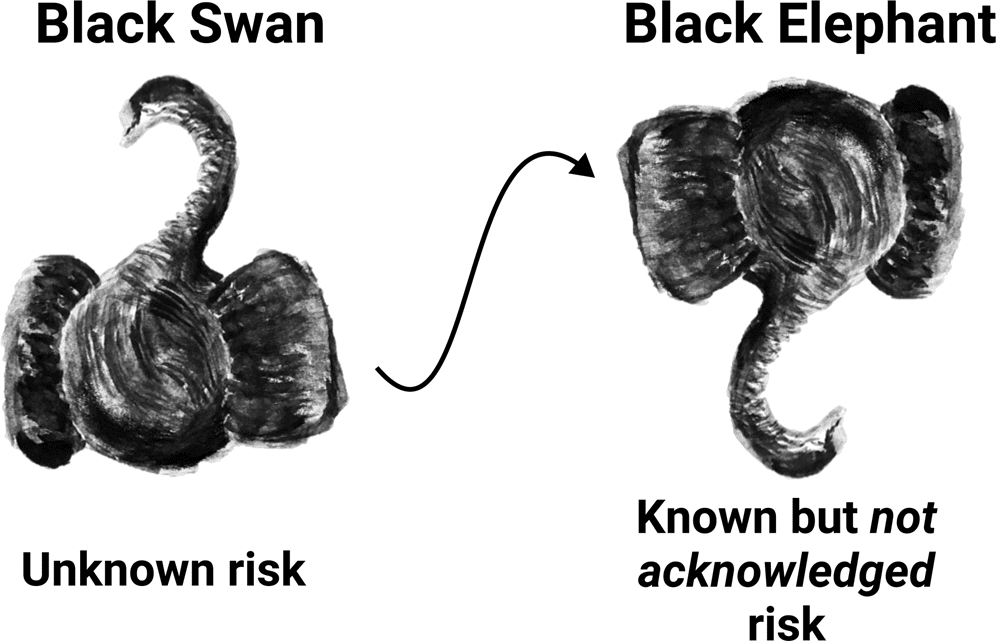

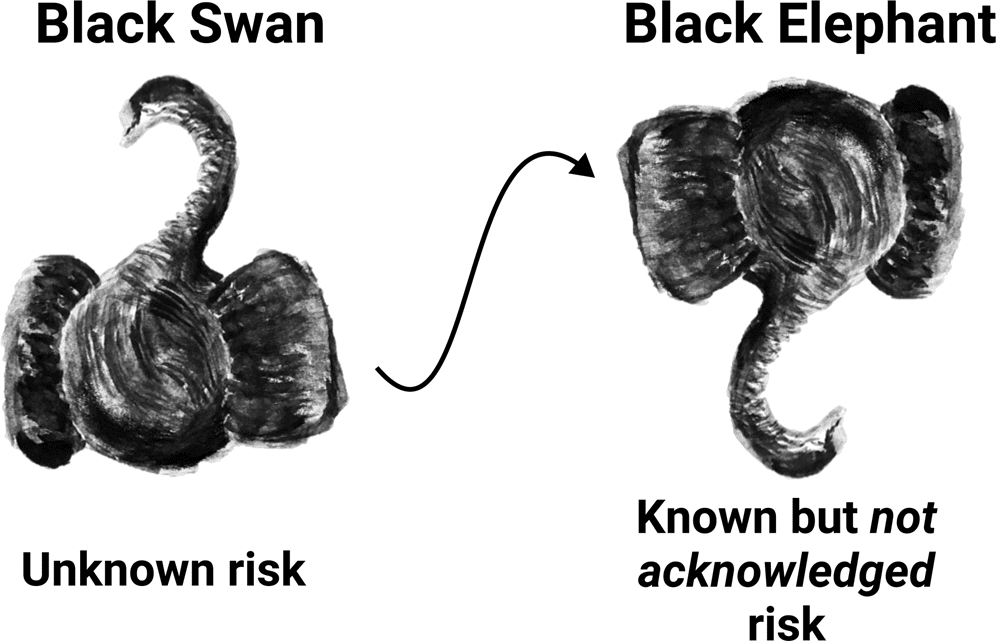

If a “black swan” event is a disaster that is unexpected, a “black elephant” is a disaster that was entirely predictable and thus avoidable. Building homes in an area prone to flooding would seem to be an obvious thing to avoid, yet local councils and developers do this constantly around New Zealand and that’s before we take into account the increasing severity of the weather events themselves.

Last year, Petone took the prize for the most talked about corner of New Zealand where we should never have built. This year, it was Glenorchy, a settlement with the highest levels of risk from liquefaction in the land, on par with the most affected parts of Christchurch after the 2011 earthquake. Not to be outdone, South Dunedin is already hugely at risk from flooding, increasingly so as the sea levels rise with discussions already starting on whether a managed retreat approach should occur. Or there’s Westport where the best level of risk from flooding you can hope for is “susceptible” while almost the entire settlement is rated as “severe”.

We have to get smarter about this, either on our own or backed by legislation and regulation if needs be. It’s one thing to say “we didn’t know about the risk when we built here,” but something else entirely to say we will continue to intensify housing in an area that is already under water. The insurance companies will simply start walking away from such areas and unfortunately for the residents, network infrastructure providers will have to ask whether it’s worth rebuilding over and over again.

Take Waka Kotahi, for example. Charged with ensuring our roading network operates, the organisation’s budget has remained static for many years even as the cost of maintaining and rebuilding continues to rise. Can it continue to maintain roads in some parts of the country, or should locals be thinking about alternatives for when the road becomes uneconomic?

These are the challenges facing infrastructure providers. This year alone has seen any number of extreme weather events both in terms of number and scale. We haven’t had an earthquake or a volcano explode but the experts say that’s a matter of when, not if, and so we must prepare.

And prepare we are. Across the various lifelines new sector-specific plans are being drawn up. The Telecommunications Emergency Management Plan (TEMP) will provide a blueprint for the telco sector to both prepare for and respond to events that require a whole sector response. We’re beginning to liaise with other critical infrastructure sectors, like electricity and fuel, because of course it’s these intersections that are so key during any critical event. We rely on electricity, they rely on fuel, fuel needs comms to operate, and so on.

The telco sector is also investing on increasing capacity and resilience around the country as part of its constant cycle of network improvements. While many infrastructure entities face decades of underspending and an infrastructure deficit, the telco sector has come off the back of more than a decade’s worth of investment both in terms of Ultrafast Broadband and the Rural Broadband Initiative. We now offer fibre out to 87% of the population and have three competing mobile network operators each with their own networks. That provides a huge amount of resilience compared with the old days of one copper network to rule us all.

Compare that with the remaining public infrastructure base which needs to spend roughly $30 billion a year for the next decade to repair and then upgrade to meet demand. That, not-insignificant challenge, is one that must be grappled with sooner rather than later.

And in the not-too-distant future, we see the opportunity for adding yet more capability. Low-earth orbit satellites (LEOs) are coming on-line and offer both direct service for those customers in rural or remote areas but also can act as mobile phone network enhancers, allowing customers to connect from almost anywhere in the country. This is all part of the “Swiss cheese” layered approach – each network choice has pros and cons but when you layer them all together you minimise the downsides as much as possible.

New Zealand may face many challenges – second only to Bangladesh – but we are also extremely good at coming together and responding in a crisis. Now we need to figure out how we can apply that same energy to solving the problem before crisis hits.